Reporting security metrics to the board is a critical function, ensuring that board members have the information they need to make informed decisions about cybersecurity risk. This guide provides a detailed roadmap for effectively communicating complex security information in a clear, concise, and actionable manner, ultimately fostering a strong partnership between the security team and the board of directors.

This guide covers all aspects of security metrics reporting, from defining essential metrics and understanding your audience to creating compelling reports and presenting them effectively. By implementing these strategies, you can transform security reporting from a compliance exercise into a strategic asset that supports business objectives and protects your organization’s valuable assets.

Defining Security Metrics for Board Reporting

Reporting security metrics to the board is a crucial aspect of demonstrating the effectiveness of a cybersecurity program and its alignment with business objectives. This section focuses on identifying and defining the essential security metrics that board members need to understand to make informed decisions regarding cybersecurity investments, risk management, and overall business strategy. It emphasizes the selection of metrics that are directly relevant to the business’s goals and risk appetite.

Critical Security Metrics for Board Members

Board members need a concise set of metrics that provide a clear picture of the organization’s security posture and its alignment with business objectives. These metrics should be easily understood, actionable, and directly linked to the organization’s key performance indicators (KPIs). They should also enable the board to assess the effectiveness of the cybersecurity program and make informed decisions about resource allocation.

The following are examples of critical security metrics, categorized by type:

- Incident Response: Time to Detect (TTD)

-The average time it takes to identify a security incident, measured from the moment the incident occurs to the moment it is detected. A shorter TTD indicates a more effective incident detection capability. For example, a company that consistently reduces its TTD from 72 hours to 12 hours over a year is demonstrating a significant improvement in its security posture. - Incident Response: Time to Contain (TTC)

-The average time it takes to contain a security incident after detection. This metric reflects the efficiency of the incident response process in preventing further damage. For example, a financial institution might track its TTC to ensure it can quickly isolate compromised systems and prevent financial losses. - Vulnerability Management: Mean Time to Remediate (MTTR)

-The average time it takes to remediate identified vulnerabilities. A lower MTTR indicates a proactive approach to vulnerability management and reduces the attack surface. For instance, an organization could aim to reduce its MTTR for critical vulnerabilities from 60 days to 30 days to align with industry best practices and regulatory requirements. - Security Awareness: Phishing Click-Through Rate – The percentage of employees who click on phishing emails in simulated phishing campaigns. This metric helps assess the effectiveness of security awareness training programs. A decreasing click-through rate over time suggests that the training is effective in educating employees about phishing threats.

- Data Protection: Data Loss Prevention (DLP) Incidents – The number of data loss prevention incidents, such as unauthorized data transfers or access attempts, that occur within a specific period. This metric helps monitor the effectiveness of data protection controls. For example, a healthcare provider might track the number of DLP incidents related to patient data to ensure compliance with HIPAA regulations.

Aligning Security Metrics with Business Goals and Risk Appetite

Aligning security metrics with business goals and risk appetite is essential for ensuring that cybersecurity investments are prioritized effectively and that the cybersecurity program supports the overall business strategy. This alignment requires a deep understanding of the organization’s business objectives, risk tolerance, and regulatory requirements. There are several approaches to achieve this alignment:

- Risk-Based Approach: This approach involves identifying and prioritizing the organization’s most critical assets and the threats that pose the greatest risk to those assets. Security metrics are then selected to measure the effectiveness of controls designed to mitigate those risks. For example, if a company’s most critical asset is its customer data, it might prioritize metrics related to data loss prevention and data breach detection.

- Goal-Based Approach: This approach focuses on aligning security metrics with specific business goals. For instance, if a business goal is to increase revenue, security metrics could be tied to metrics like the availability of critical systems, ensuring they are operational to facilitate transactions. If a business goal is to enter a new market, security metrics might focus on compliance with relevant regulations in that market.

- Framework-Based Approach: Utilizing established frameworks such as NIST Cybersecurity Framework or ISO 27001 can help to define security metrics and ensure a comprehensive approach to cybersecurity management. These frameworks provide a standardized set of controls and metrics that can be tailored to the organization’s specific needs.

- Regular Review and Adjustment: Security metrics should be regularly reviewed and adjusted to reflect changes in the business environment, threat landscape, and regulatory requirements. This ensures that the metrics remain relevant and effective in supporting business objectives. This review process could involve quarterly or annual assessments to ensure that the metrics are still providing meaningful insights.

Identifying Your Audience: The Board of Directors

Understanding the board of directors is paramount for effective security reporting. Board members, while possessing diverse backgrounds, typically share a common need for concise, relevant information presented in a manner that facilitates informed decision-making. Tailoring security reports to their specific needs and interests is crucial for gaining their support and securing necessary resources.

Information Needs and Technical Understanding of Board Members

Board members typically require high-level overviews, focusing on strategic implications rather than granular technical details. They need to understand the organization’s overall security posture, key risks, and the effectiveness of mitigation strategies. While the level of technical understanding varies, most board members are not cybersecurity experts. Reports should avoid jargon and complex technical explanations, focusing instead on the business impact of security issues.

- Key Information Needs: Board members typically need information regarding:

- Strategic Alignment: How security aligns with the organization’s overall business strategy and objectives.

- Risk Exposure: The nature and likelihood of significant security risks, along with their potential financial and reputational impacts.

- Mitigation Effectiveness: The effectiveness of implemented security controls and programs in reducing risk.

- Compliance: The organization’s compliance with relevant regulations and industry standards.

- Resource Allocation: The allocation of resources (budget, personnel) to security initiatives and their return on investment.

- Level of Technical Understanding:

- Focus on Business Impact: Reports should prioritize the business impact of security issues, rather than technical details.

- Use of Analogies: Employing analogies and real-world examples can help bridge the gap in technical understanding. For instance, comparing cybersecurity to physical security, such as a lock on a door, can simplify complex concepts.

- Visualizations: Charts, graphs, and dashboards can effectively communicate complex data and trends.

Reporting Needs of Different Board Committees

Different board committees have distinct priorities and reporting needs related to security. Understanding these nuances allows for the creation of targeted reports that resonate with each committee’s specific responsibilities.

- Audit Committee: The audit committee is primarily concerned with the effectiveness of internal controls, regulatory compliance, and financial reporting. Security reports to this committee should focus on:

- Compliance with Regulations: Reports should detail the organization’s compliance with relevant regulations such as GDPR, CCPA, HIPAA, and industry standards like PCI DSS.

- Internal Control Effectiveness: Assessment of the effectiveness of security controls in mitigating risks that could impact financial reporting or operations.

- Audit Findings and Remediation: Details of security audit findings, the steps taken to remediate them, and the associated timelines.

- Example: A report might include a table showing the status of compliance with PCI DSS requirements, highlighting any gaps and the planned remediation activities.

- Risk Committee: The risk committee is responsible for overseeing the organization’s risk management framework, including cybersecurity risk. Reports to this committee should emphasize:

- Risk Assessment and Mitigation: A summary of the organization’s cybersecurity risk assessment process, the identified risks, and the effectiveness of mitigation strategies.

- Risk Appetite: Discussion of the organization’s risk appetite and whether the current security posture aligns with it.

- Incident Response and Business Continuity: Updates on incident response plans, business continuity plans, and the results of any exercises or simulations.

- Example: A report might present a risk register, showing the likelihood and impact of various cyber threats, along with the implemented controls to reduce those risks.

- Technology Committee (if applicable): The technology committee focuses on the organization’s technology strategy, including cybersecurity. Reports to this committee should delve deeper into technical aspects while still maintaining a business focus:

- Technology Investments: Updates on investments in security technologies, their performance, and their alignment with the organization’s security strategy.

- Security Architecture: Overview of the organization’s security architecture and any planned changes or upgrades.

- Emerging Threats and Technologies: Discussion of emerging cybersecurity threats and technologies, and their potential impact on the organization.

- Example: A report might include a dashboard showing the performance of the organization’s security information and event management (SIEM) system, highlighting any unusual activity or trends.

Tailoring Security Reports to the Board’s Interests and Concerns

To ensure that security reports resonate with the board, it’s crucial to tailor them to their specific areas of interest and concerns. This involves understanding their priorities, anticipating their questions, and presenting information in a clear and concise manner.

- Understand Board Priorities:

- Review Board Minutes: Analyze past board minutes to identify the issues and concerns that have been raised in the past.

- Conduct Interviews: If possible, conduct brief interviews with board members to understand their specific interests and information needs.

- Monitor Industry Trends: Stay informed about industry trends, regulatory changes, and emerging threats that may be of interest to the board.

- Address Specific Concerns:

- Reputational Risk: If the board is particularly concerned about reputational risk, security reports should highlight the potential impact of security incidents on the organization’s brand and public image.

- Financial Impact: If the board is focused on financial performance, security reports should quantify the potential financial losses associated with security incidents, such as data breaches, ransomware attacks, and business disruptions.

- Regulatory Compliance: If the organization operates in a highly regulated industry, security reports should emphasize the organization’s compliance with relevant regulations and the potential penalties for non-compliance.

- Provide Concrete Examples:

- Real-World Incidents: Include examples of real-world security incidents and their impact on other organizations.

- Quantitative Data: Use data and metrics to illustrate the organization’s security posture and the effectiveness of security controls.

- Visualizations: Use charts, graphs, and dashboards to communicate complex data in a clear and concise manner.

- Example 1: A report on ransomware attacks might include data on the number of attacks, the average ransom demand, and the potential cost of downtime. The report can also provide a graph showing the organization’s vulnerability to ransomware attacks.

- Example 2: A report on data breaches might include information on the number of records exposed, the types of data compromised, and the potential costs of notification, legal fees, and remediation. The report can also show a comparison of the organization’s breach response time with industry averages.

Selecting the Right Metrics

Choosing the right security metrics to report to the board is crucial for effective communication and informed decision-making. The focus should be on metrics that provide actionable insights, align with business objectives, and clearly demonstrate the value of the security program. This section Artikels the key criteria, prioritization framework, and strategies to avoid misleading ‘vanity metrics.’

Key Criteria for Selecting Metrics

Selecting relevant and actionable metrics involves considering several key factors. These factors ensure that the board receives information that is both meaningful and directly applicable to strategic decision-making.

- Relevance to Business Objectives: Security metrics must directly relate to the organization’s overall goals and strategic priorities. For example, if the business is focused on e-commerce growth, metrics related to transaction security and fraud prevention are paramount.

- Actionability: Metrics should provide insights that lead to specific actions. They must highlight areas of strength and weakness, enabling the board to understand the impact of security investments and the effectiveness of security controls.

- Clarity and Understandability: Metrics need to be presented in a clear, concise, and easily understandable manner, avoiding technical jargon that might confuse non-technical board members. Visualizations, such as charts and graphs, can significantly improve comprehension.

- Alignment with Risk Appetite: The selected metrics should reflect the organization’s risk appetite and tolerance levels. They should help the board understand whether the current level of security risk is acceptable.

- Measurability and Data Availability: Metrics must be measurable and based on reliable, readily available data. If the data collection process is complex or the data is unreliable, the value of the metric is diminished.

Prioritizing Metrics for Impact and Risk Reduction

Prioritizing security metrics involves creating a framework to evaluate and rank metrics based on their potential impact on business outcomes and risk reduction. This framework helps ensure that the board focuses on the most critical aspects of the security program.

One effective approach is to use a matrix that considers both the impact of a security incident and the likelihood of its occurrence. This can be visualized as a risk matrix, where:

- High Impact, High Likelihood: These represent the most critical risks, requiring immediate attention and robust mitigation strategies. Metrics related to these risks should be prioritized for board reporting.

- High Impact, Low Likelihood: These risks still require attention but might not warrant the same level of immediate action as high-likelihood risks.

- Low Impact, High Likelihood: These risks are often manageable through routine security practices and controls.

- Low Impact, Low Likelihood: These risks may require monitoring but are generally of lower priority.

Another method involves assessing the potential financial impact of a security breach. This can be quantified using the following formula:

Annualized Loss Expectancy (ALE) = Single Loss Expectancy (SLE) x Annual Rate of Occurrence (ARO)

Where:

- SLE is the financial loss expected from a single occurrence of a security incident.

- ARO is the estimated number of times the incident is expected to occur in a year.

Metrics related to risks with a high ALE should be prioritized.

For example, consider a company that processes credit card transactions. A potential metric is the number of successful phishing attacks against employees. If a successful phishing attack leads to a data breach (high impact) and phishing attempts are frequent (high likelihood), this metric should be prioritized. The board should receive regular updates on the effectiveness of phishing training and other related security controls.

Avoiding Vanity Metrics

‘Vanity metrics’ are those that look impressive on the surface but do not provide meaningful insights into the effectiveness of the security program or its impact on business outcomes. Avoiding these metrics is crucial for ensuring that board discussions are focused and productive.

Examples of vanity metrics and their more meaningful alternatives:

| Vanity Metric | Why It’s Misleading | More Meaningful Alternative | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of vulnerabilities scanned | Doesn’t reflect the severity of vulnerabilities or the effectiveness of remediation efforts. | Percentage of critical vulnerabilities remediated within a defined timeframe. | Focuses on addressing the most significant risks and demonstrates proactive risk management. |

| Number of security alerts generated | Doesn’t indicate the actual number of security incidents or the effectiveness of incident response. | Number of confirmed security incidents and the time to detect and respond to those incidents. | Provides a clear picture of the organization’s security posture and incident response capabilities. |

| Number of security training sessions conducted | Doesn’t measure the effectiveness of the training in changing employee behavior. | Phishing click-through rates before and after training, and the percentage of employees who can identify phishing attempts. | Demonstrates the tangible impact of security awareness programs. |

To avoid vanity metrics, focus on:

- Business-aligned metrics: Metrics that directly support business objectives, such as the reduction in fraud losses or the improvement in customer trust.

- Outcome-based metrics: Metrics that measure the actual results of security efforts, such as the time to detect and contain a security incident.

- Leading indicators: Metrics that provide early warnings of potential security issues, such as the number of failed login attempts or the volume of suspicious network traffic.

Data Collection and Preparation

Collecting and preparing data is a critical phase in security metric reporting. The quality of your data directly impacts the credibility and usefulness of your reports to the board. A well-defined data collection and preparation process ensures that the metrics accurately reflect your organization’s security posture and that the board receives reliable information for decision-making.

Data Sources and Tools for Security Metrics

The process of gathering security data requires a strategic approach, considering the diverse sources from which information originates and the appropriate tools to collect and manage it effectively.Data sources include:

- Security Information and Event Management (SIEM) Systems: SIEM systems are a primary source, aggregating logs from various sources such as firewalls, intrusion detection systems (IDS), endpoint detection and response (EDR) solutions, and servers. They provide valuable data on security incidents, threats, and vulnerabilities.

- Vulnerability Scanners: These tools, such as Nessus or OpenVAS, scan systems and applications to identify known vulnerabilities. The data collected includes vulnerability severity, affected assets, and remediation status.

- Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR) Solutions: EDR solutions offer detailed insights into endpoint activities, including malware detection, suspicious behavior, and policy violations. They provide data on security incidents and potential threats.

- Firewalls and Intrusion Detection/Prevention Systems (IDS/IPS): These systems generate logs that provide information on network traffic, attempted attacks, and security policy violations.

- Cloud Security Posture Management (CSPM) Tools: For organizations using cloud services, CSPM tools monitor cloud configurations, identify misconfigurations, and assess compliance with security best practices.

- Identity and Access Management (IAM) Systems: IAM systems provide data on user access, authentication attempts, and authorization controls. This data is crucial for understanding access-related risks.

- Help Desk Ticketing Systems: These systems record security-related incidents reported by users, such as phishing attempts or suspicious emails.

- Asset Management Systems: Asset management systems provide information on the organization’s IT assets, including hardware, software, and their configurations. This data is essential for assessing the impact of vulnerabilities and security incidents.

Tools used for data collection include:

- SIEM tools: Such as Splunk, QRadar, and Microsoft Sentinel, which aggregate and analyze security logs from various sources.

- Vulnerability scanners: Such as Nessus and OpenVAS, which identify and report vulnerabilities.

- Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR) solutions: Such as CrowdStrike and SentinelOne, which monitor and respond to threats on endpoints.

- Network monitoring tools: Such as Wireshark and SolarWinds Network Performance Monitor, which capture and analyze network traffic.

- Cloud security tools: Such as AWS Security Hub and Azure Security Center, which provide security insights for cloud environments.

- Data connectors and APIs: Custom scripts or third-party connectors can be used to collect data from various sources and integrate it into a central reporting platform.

Data Preparation for Board Reports

Preparing data for board reports involves a series of steps to ensure its accuracy, relevance, and clarity. This process includes cleaning, validation, and aggregation.The step-by-step guide includes:

- Data Cleaning:

- Remove irrelevant or redundant data: Eliminate unnecessary data fields or log entries that do not contribute to the selected metrics.

- Standardize data formats: Ensure consistent formatting across all data sources for dates, times, IP addresses, and other critical fields.

- Handle missing values: Decide how to address missing data points. Options include imputation (e.g., using averages) or exclusion, depending on the metric and the extent of missing data.

- Correct errors: Identify and correct any data entry errors or inconsistencies.

- Data Validation:

- Verify data integrity: Check for inconsistencies, outliers, and anomalies in the data. For example, look for unusual spikes in the number of security incidents or unusually high values for vulnerability severity scores.

- Cross-validate data from multiple sources: Compare data from different sources to ensure consistency and identify potential discrepancies. For instance, compare the number of security incidents reported by the SIEM with the number of incidents reported by the help desk.

- Implement data validation rules: Define and enforce rules to check the data for accuracy and completeness. For example, ensure that all IP addresses are valid and that dates are within the expected range.

- Data Aggregation:

- Aggregate data based on the selected metrics: Calculate the required metrics by summarizing and grouping data from various sources. For example, calculate the number of successful phishing attempts, the average time to patch vulnerabilities, or the percentage of systems compliant with security policies.

- Use appropriate aggregation methods: Choose the right aggregation methods (e.g., sums, averages, percentages) based on the nature of the data and the specific metrics being reported.

- Group data by relevant categories: Group data by different categories, such as asset type, business unit, or risk level, to provide a more granular view of the security posture.

Addressing Data Quality Issues and Ensuring Accuracy

Data quality issues can undermine the reliability of security metrics and lead to inaccurate reporting. It is important to proactively address these issues to ensure the accuracy of reported metrics.Addressing data quality issues and ensuring accuracy involves the following:

- Implement Data Quality Controls: Establish data quality controls to monitor and improve the accuracy of the data. These controls include:

- Data validation rules: Define rules to check data for accuracy and completeness. For example, ensure that all IP addresses are valid and that dates are within the expected range.

- Data quality dashboards: Create dashboards to visualize data quality metrics, such as the percentage of missing data or the number of data entry errors.

- Regular data audits: Conduct periodic audits to identify and correct data quality issues.

- Common Data Quality Issues and Mitigation Strategies:

- Incomplete Data: Address this by ensuring data sources are configured correctly to capture all relevant information. Implement data validation rules to identify and flag missing data points.

- Inconsistent Data: Standardize data formats across all data sources. Use data transformation techniques to ensure consistency.

- Inaccurate Data: Implement data validation rules to identify and correct errors. Regularly review data entry processes and provide training to data entry personnel.

- Outdated Data: Implement processes to ensure that data is updated regularly. Automate data collection and processing as much as possible.

- Duplicate Data: Identify and remove duplicate data entries. Implement data deduplication processes.

- Accuracy and Validation Techniques:

- Triangulation: Cross-validate data from multiple sources to ensure consistency. For example, compare the number of security incidents reported by the SIEM with the number of incidents reported by the help desk and EDR tools.

- Statistical Analysis: Use statistical methods to identify outliers and anomalies in the data. For example, use control charts to monitor the number of security incidents over time and identify any unusual spikes.

- Manual Review: Regularly review the data manually to identify and correct any errors or inconsistencies.

For example, consider a scenario where a company reports on the “Time to Patch Critical Vulnerabilities” metric. If the vulnerability scanner consistently reports the same vulnerabilities as unpatched, but the patching system indicates they are patched, this indicates a data quality issue. Resolving this requires investigating the data sources, verifying the patching process, and ensuring that both systems are accurately reflecting the current state of the environment.

Reporting Frequency and Timing

Establishing a consistent and timely reporting cadence is crucial for keeping the board informed about the organization’s security posture. This section details the optimal frequency for reporting, aligns the reporting schedule with the board’s meeting cycle, and provides guidelines for handling urgent security incidents. Effective communication ensures the board can make informed decisions and provide strategic oversight of cybersecurity risks.

Optimal Reporting Frequency

Determining the right reporting frequency balances the need for regular updates with the board’s limited time and attention. The ideal frequency depends on several factors, including the organization’s size, industry, risk profile, and the board’s specific requirements. Industry best practices often recommend a quarterly reporting cycle as a baseline. However, more frequent reporting may be necessary for organizations facing higher threat levels or significant regulatory scrutiny.

- Quarterly Reporting: This is the most common reporting frequency. It provides a comprehensive overview of the security program’s performance, including key metrics, risk assessments, and incident summaries. This aligns well with the typical cadence of board meetings.

- Monthly Reporting (for high-risk environments): Organizations in highly regulated industries (e.g., finance, healthcare) or those experiencing frequent security incidents might benefit from monthly reports. This allows for more timely communication of emerging risks and proactive decision-making.

- Annual Reporting: Annual reports can provide a high-level summary of the year’s security activities, strategic initiatives, and overall program effectiveness. This is usually insufficient as a standalone reporting frequency but can serve as a valuable supplement to quarterly or monthly reports.

Aligning Reporting with the Board’s Meeting Cycle

The reporting schedule should be synchronized with the board’s meeting calendar to ensure that security information is discussed at the appropriate times. This facilitates timely decision-making and allows for strategic oversight.

- Schedule Adherence: Reports should be prepared and distributed well in advance of board meetings, typically at least one week prior. This allows board members sufficient time to review the information and prepare any questions.

- Meeting Agendas: Security metrics and updates should be a standing item on the board’s agenda. This underscores the importance of cybersecurity and ensures it receives consistent attention.

- Executive Summaries: Each report should include a concise executive summary highlighting the key findings, trends, and recommendations. This helps board members quickly grasp the most critical information.

Handling Urgent Security Incidents

Urgent security incidents require immediate communication to the board, irrespective of the regular reporting schedule. Clear guidelines and protocols are essential for ensuring a swift and effective response.

- Incident Escalation Protocols: Establish a clear escalation path for security incidents, outlining the criteria that trigger board notification. These criteria should include incidents with significant financial impact, data breaches involving sensitive information, or those that could damage the organization’s reputation.

- Communication Methods: Use multiple communication channels (e.g., email, phone calls, secure messaging) to ensure the board receives timely updates. A well-defined communication plan, including contact information for key board members, is crucial.

- Incident Reports: Prepare concise incident reports that include the following:

- A brief description of the incident.

- The impact on the organization (e.g., data compromised, system downtime).

- Actions taken to contain and remediate the incident.

- The status of the investigation.

- Recommendations for preventing future incidents.

- Examples:

- Data Breach: If a significant data breach occurs involving customer credit card information, the board should be notified immediately. This would trigger an immediate response, potentially involving external legal counsel and public relations support.

- Ransomware Attack: If a ransomware attack cripples critical systems, the board needs immediate updates on the attack’s progress, potential ransom demands, and the organization’s recovery plan.

Creating Effective Reports

Presenting security metrics effectively to the board requires more than just data; it demands clarity, impact, and a compelling narrative. The goal is to transform complex technical information into actionable insights that board members can readily understand and use to make informed decisions. This section will explore how to design effective reports, utilize data visualizations, and employ storytelling techniques to achieve this objective.

Designing Effective Report Formats

A well-designed report format is crucial for ensuring that security metrics are easily digestible and actionable. The format should be visually appealing, concise, and tailored to the board’s needs.A key aspect of report design involves the use of tables to present key metrics in a clear and organized manner. Tables allow for the efficient display of numerical data and trends, making it easier for board members to grasp the overall security posture.

Consider using a table format with responsive columns for optimal viewing on various devices.Here’s an example of a sample table layout:

| Metric Category | Metric Name | Current Value | Trend |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vulnerability Management | Mean Time to Remediate (MTTR) Critical Vulnerabilities | 14 days | Increased by 2 days this quarter |

| Incident Response | Number of Security Incidents Detected | 12 | Decreased by 2 incidents this quarter |

| Access Control | Percentage of Users with Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA) Enabled | 95% | Increased by 5% this quarter |

| Compliance | Percentage of Systems Compliant with Security Policies | 90% | Remained stable this quarter |

The table above uses a simple, clear structure. Each row represents a key security metric, categorized for easy understanding. The “Current Value” column provides the latest measurement, and the “Trend” column indicates whether the metric is improving, declining, or remaining stable. This format allows board members to quickly identify areas of concern and track progress over time. The use of responsive columns ensures the table adapts to different screen sizes, making it accessible on various devices.

Data Visualizations for Effective Communication

Data visualizations are essential for effectively communicating security risks and performance. Charts and graphs transform raw data into easily understandable formats, allowing board members to quickly grasp complex information and identify trends.

- Line Charts: Line charts are excellent for illustrating trends over time. For example, a line chart can show the number of phishing attacks detected each month over the past year, highlighting any increases or decreases. This visualization helps the board understand the evolving threat landscape.

- Bar Charts: Bar charts are ideal for comparing different categories of data. For instance, a bar chart can compare the number of security incidents by type (e.g., malware, phishing, data breach), providing a clear overview of the most prevalent threats.

- Pie Charts: Pie charts are useful for displaying proportions or percentages. A pie chart can illustrate the distribution of security incidents across different departments or business units, revealing which areas are most vulnerable.

- Heatmaps: Heatmaps can visually represent complex data, such as the risk associated with different systems or applications. Using a color-coded system, heatmaps can highlight areas of high risk, allowing the board to quickly identify critical vulnerabilities. For example, a heatmap could show the vulnerability scores of different servers, with red indicating high-risk servers and green indicating low-risk servers.

A compelling example of data visualization effectiveness comes from the Verizon Data Breach Investigations Report (DBIR). Their consistent use of various charts and graphs (bar charts for incident types, line charts for trend analysis, and pie charts for data breach patterns) simplifies complex data, allowing stakeholders to understand the key trends and patterns in cybersecurity incidents.

Storytelling with Data

Transforming technical information into actionable insights involves storytelling with data. This means presenting security metrics not just as numbers, but as a narrative that highlights the significance of the data and its implications for the organization.

- Contextualize the Data: Begin by providing context. Explain the relevance of the metrics to the organization’s overall business objectives and risk profile. For instance, when presenting data on phishing attacks, explain how these attacks could potentially impact revenue or reputation.

- Highlight Key Findings: Focus on the most important findings. Instead of overwhelming the board with all the data, select the key metrics that are most critical to the organization’s security posture. Emphasize any significant trends, anomalies, or areas of concern.

- Provide Actionable Recommendations: Translate the data into actionable recommendations. Clearly state what actions the board needs to take based on the findings. For example, if the data shows a significant increase in ransomware attacks, recommend investing in enhanced endpoint detection and response (EDR) solutions or employee security awareness training.

- Use Plain Language: Avoid technical jargon. Explain the metrics in plain language that the board can easily understand. Use analogies and real-world examples to illustrate the concepts.

- Focus on Impact: Emphasize the potential impact of the security risks on the organization. This helps the board understand the importance of the security measures and the potential consequences of inaction. For example, quantify the potential financial losses or reputational damage associated with a data breach.

An example of successful storytelling can be seen in the reports of publicly traded companies. When reporting on cybersecurity risks, they often don’t just state the number of incidents; they explain thepotential* impact on their financial performance, legal liabilities, and brand reputation. They provide context, highlight key risks, and present actionable steps to mitigate them. This approach ensures that the board understands the strategic importance of cybersecurity and its impact on the company’s overall success.

Presenting to the Board

Presenting security metrics to the board is a critical opportunity to communicate the organization’s security posture and demonstrate the value of the security program. Effective presentation skills, a clear understanding of the board’s perspective, and the ability to handle questions are essential for success. This section provides guidance on communication strategies for presenting security metrics to the board.

Communication Tone and Language

The tone and language used in presentations to the board should be professional, clear, and concise. Avoid technical jargon that the board may not understand. Focus on conveying the key takeaways and their implications for the business.

- Maintain a professional and confident demeanor: Projecting confidence in your knowledge and the security program builds trust.

- Use plain language: Avoid technical jargon and acronyms. Define any terms that are essential but unfamiliar to the audience.

- Focus on business impact: Frame security metrics in terms of their impact on the organization’s strategic objectives, financial performance, and reputation. For example, instead of saying “We detected 100 phishing attempts,” say “We prevented a potential financial loss of $X from phishing attacks by proactively blocking these attempts.”

- Be transparent and honest: Acknowledge both successes and challenges. If there are areas of concern, explain the situation, the steps being taken to address it, and the expected outcomes.

- Tailor the presentation to the audience: Consider the board members’ backgrounds and areas of expertise. Adjust the level of detail and the focus of the presentation accordingly. For example, if the board includes members with strong financial backgrounds, include metrics related to the cost of security incidents and the return on investment (ROI) of security investments.

Handling Questions and Challenges

Board members may have questions or concerns about the security program. Prepare for these by anticipating potential questions and developing clear, concise responses. Demonstrate a willingness to engage in a dialogue and provide additional information as needed.

- Listen carefully: Pay close attention to the question being asked to ensure you understand the board member’s concerns.

- Acknowledge the question: Start by acknowledging the question, even if it seems challenging. For example, “That’s a valid question, and I appreciate you bringing it up.”

- Provide a clear and concise answer: Get straight to the point and avoid rambling. Use plain language and avoid technical jargon.

- Back up your answer with data: Support your responses with data, evidence, and relevant metrics. For example, if asked about the effectiveness of a security control, provide statistics on its performance, such as the number of threats blocked or the reduction in incident response time.

- Be prepared to say “I don’t know”: If you don’t know the answer, it’s better to admit it than to guess or provide inaccurate information. Offer to follow up with the information.

- Address concerns proactively: If you anticipate a particular concern, address it directly in your presentation. For example, if you know that the board is concerned about ransomware, include a section on your ransomware prevention and response plan.

- Stay calm and professional: Even if the questions are challenging or critical, maintain a calm and professional demeanor. Avoid becoming defensive.

- Offer solutions, not just problems: When discussing challenges, focus on the solutions being implemented to address them. For example, if there has been an increase in phishing attacks, describe the steps being taken to improve employee training and enhance email security controls.

Effective Use of Visuals and Supporting Documentation

Visual aids and supporting documentation can enhance the clarity and impact of your presentation. Use visuals to illustrate key metrics, trends, and relationships. Provide supporting documentation to back up your claims and provide additional detail.

- Use clear and concise visuals: Avoid cluttered slides with too much text. Use charts, graphs, and diagrams to illustrate key data points and trends. For example, a bar chart can effectively show the number of security incidents over time, or a pie chart can represent the distribution of incident types.

- Choose the right chart type: Different chart types are suitable for different types of data. Line charts are useful for showing trends over time, bar charts for comparing categories, and pie charts for showing proportions.

- Label visuals clearly: Ensure that all visuals are clearly labeled with titles, axis labels, and legends. This makes it easier for the board to understand the information being presented.

- Use consistent formatting: Maintain a consistent look and feel across all visuals. This makes the presentation more professional and easier to follow.

- Provide supporting documentation: Prepare a written report or supporting documentation that provides more detail on the metrics being presented. This documentation can include definitions of terms, methodologies, and additional data points. This document can be a PDF or printed handout.

- Have documentation available: Make sure the supporting documentation is readily available for the board to review before, during, or after the presentation.

- Illustrative Example:

Imagine a slide displaying a line graph showing the trend of successful phishing attacks over the past year. The x-axis represents months, and the y-axis represents the number of successful attacks. The line shows a spike in the number of attacks during a particular month. A corresponding bullet point on the slide highlights the specific month and the cause, such as a new phishing campaign exploiting a recently discovered vulnerability.

Beneath the graph, a brief description of the mitigation steps taken, such as increased employee training and implementation of enhanced email filtering, would be present. The accompanying documentation would include detailed statistics on phishing attempts, blocked emails, and the cost of the attacks.

Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) vs. Key Risk Indicators (KRIs)

Understanding the distinction between Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) and Key Risk Indicators (KRIs) is crucial for effective security reporting to the board. While both are essential for monitoring and managing security posture, they serve different purposes and provide distinct insights. KPIs measure the success of security initiatives, while KRIs proactively highlight potential risks and vulnerabilities. This section clarifies the roles of each and provides practical examples for board reporting.

Comparing and Contrasting KPIs and KRIs

KPIs and KRIs offer complementary perspectives on an organization’s security health. KPIs focus on measuring the achievement of security objectives, often reflecting the effectiveness of implemented controls and processes. KRIs, on the other hand, are forward-looking, designed to identify and monitor potential risks before they materialize into incidents.The primary difference lies in their focus:* KPIs (Key Performance Indicators): Measure the

- effectiveness* of security measures and initiatives. They assess how well the organization is achieving its security goals. They are generally

- lagging* indicators, reflecting past performance.

- likelihood* and

- impact* of potential risks. They are designed to provide

- early warning* signals of potential security incidents, enabling proactive risk management. They are generally

- leading* indicators.

KRIs (Key Risk Indicators)

Measure the

The table below summarizes the key differences:

| Feature | KPIs | KRIs |

|---|---|---|

| Objective | Measure performance and success. | Identify and monitor potential risks. |

| Focus | Effectiveness of security controls and processes. | Likelihood and impact of risks. |

| Nature | Lagging indicators (reflect past performance). | Leading indicators (provide early warning). |

| Purpose | Track progress towards security goals. | Enable proactive risk management. |

Examples of KPIs and KRIs for Board Reporting

Selecting the right KPIs and KRIs is critical for providing the board with meaningful insights. The following examples illustrate common metrics relevant for security reporting: KPIs (Key Performance Indicators):* Mean Time to Detect (MTTD): This metric measures the average time it takes to identify a security incident, from the time it occurs to the time it is detected. A decreasing MTTD indicates improvements in detection capabilities.

For example, if the MTTD decreased from 72 hours to 24 hours, it reflects enhanced detection capabilities.

Mean Time to Respond (MTTR)

This metric measures the average time it takes to contain and remediate a security incident. A decreasing MTTR indicates improvements in incident response efficiency. If MTTR is reduced from 48 hours to 12 hours, it reflects a faster incident resolution process.

Number of Phishing Attacks Blocked

This metric tracks the effectiveness of anti-phishing measures. A high number of blocked phishing attacks suggests a robust email security system.

Percentage of Systems Patched Within SLA

This KPI measures the timeliness of patching vulnerabilities. A high percentage indicates good vulnerability management practices.

Security Awareness Training Completion Rate

This metric tracks employee participation in security awareness training. A high completion rate suggests a more security-conscious workforce. KRIs (Key Risk Indicators):* Number of Unpatched Critical Vulnerabilities: This KRI identifies the number of systems with unpatched vulnerabilities that are deemed critical. An increasing number could signal a higher risk of exploitation.

Number of Failed Logins

This metric monitors the number of failed login attempts. A sudden increase might indicate a brute-force attack.

Percentage of Users with Privileged Access

This KRI monitors the proportion of users with elevated access rights. A high percentage could indicate a potential insider threat.

Number of Suspicious Network Events

This KRI tracks the number of unusual network activities. A sudden spike could signal a compromise.

Time to Patch Known Vulnerabilities (Exceeding SLA)

This KRI monitors the number of times the organization has failed to patch known vulnerabilities within the agreed-upon service level agreement (SLA). This metric helps to identify trends in patching delays and associated risks.

Establishing Thresholds and Triggers for KRIs

Establishing thresholds and triggers is essential for proactively managing risks. These thresholds define acceptable and unacceptable levels of risk, triggering alerts and actions when exceeded.Here’s a step-by-step approach:

1. Define the KRI

Clearly define the metric being tracked (e.g., Number of Unpatched Critical Vulnerabilities).

2. Set Baseline

Determine the normal or expected level of the KRI based on historical data and industry benchmarks.

3. Establish Thresholds

Define acceptable (green), warning (yellow), and critical (red) thresholds.

Green

The KRI is within acceptable limits. No action is needed.

Yellow

The KRI is approaching the threshold. Increased monitoring and investigation may be necessary.

Red

The KRI has exceeded the threshold. Immediate action is required to mitigate the risk.

4. Define Triggers

Specify the events or conditions that will trigger alerts and actions when a threshold is breached. For example, if the number of unpatched critical vulnerabilities exceeds a certain number, an alert should be sent to the security team.

5. Define Actions

Specify the actions to be taken when a threshold is breached. These actions might include:

Escalation to the security team or other relevant stakeholders.

Initiating incident response procedures.

Conducting a risk assessment.

Implementing additional security controls.

6. Regularly Review and Adjust

Periodically review and adjust thresholds and triggers based on changes in the threat landscape, business operations, and the effectiveness of existing controls.For example, consider the KRI “Number of Unpatched Critical Vulnerabilities.”* KRI: Number of Unpatched Critical Vulnerabilities

Baseline

0-2

Thresholds

Green

0-2 vulnerabilities

Yellow

3-5 vulnerabilities

Red

6+ vulnerabilities

Triggers

Yellow

Alert to the security team.

Red

Alert to the security team, incident response plan activated, and escalation to management.

Actions

Yellow

Review patching status, prioritize patching efforts.

Red

Immediate patching efforts, risk assessment, and potential temporary system shutdown.By establishing and monitoring KRIs with defined thresholds and triggers, organizations can proactively manage risks, enabling timely intervention and reducing the potential impact of security incidents. This approach provides valuable insights to the board, demonstrating a proactive and risk-aware security posture.

Benchmarking and Industry Comparisons

Reporting security metrics to the board becomes significantly more impactful when contextualized within the broader industry landscape. Benchmarking allows for a comparative analysis of your organization’s security posture against its peers, providing valuable insights into areas of strength and weakness. This comparative perspective is crucial for informed decision-making, resource allocation, and strategic planning.

Importance of Benchmarking Security Performance

Benchmarking provides a vital framework for evaluating security performance beyond internal metrics. It allows the board to understand the organization’s relative position within its industry, identify potential vulnerabilities, and gauge the effectiveness of security investments. This comparative analysis is critical for several reasons:

- Risk Prioritization: Benchmarking helps prioritize security risks based on their impact relative to industry trends. If a particular risk is more prevalent or impactful in your industry, it warrants increased attention.

- Resource Allocation: By comparing security spending and resource allocation with industry peers, the board can ensure that investments are appropriately aligned with the organization’s risk profile and strategic objectives.

- Performance Evaluation: Benchmarking provides a basis for evaluating the effectiveness of security controls and programs. It helps determine whether the organization is meeting or exceeding industry standards.

- Strategic Decision-Making: Benchmarking data informs strategic decisions related to security investments, technology adoption, and the overall security strategy.

Methods for Identifying Benchmarks and Gathering Comparative Data

Identifying relevant benchmarks and gathering comparative data requires a systematic approach. The process typically involves identifying key performance indicators (KPIs) and key risk indicators (KRIs) that are relevant to the industry and organization, then collecting and analyzing data from various sources.

- Industry Reports and Surveys: Many organizations publish industry-specific security reports and surveys that provide valuable benchmarking data. These reports often cover a range of topics, including security spending, incident rates, and control effectiveness.

For example, the Verizon Data Breach Investigations Report (DBIR) provides detailed analysis of data breaches, including industry-specific trends and statistics. Other sources include reports from Gartner, Forrester, and SANS Institute.

- Peer Group Analysis: Identify a peer group of organizations that are similar in size, industry, and business model. Gathering data from these peers can provide a more targeted and relevant comparison.

This can be achieved through direct engagement with peers, industry associations, or by leveraging data from security service providers that aggregate data from their client base, ensuring data privacy is maintained.

- Security Service Providers: Security service providers often have access to a wealth of benchmarking data based on their client engagements. They can provide insights into industry best practices and performance metrics.

These providers can also assist in collecting and analyzing data, and in interpreting the results in the context of your organization’s specific risk profile. Using a provider can ensure data confidentiality and accuracy.

- Government and Regulatory Agencies: Government agencies and regulatory bodies may publish data related to security incidents, compliance, and best practices.

For example, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) provides frameworks and guidelines that can be used for benchmarking security controls.

- Data Privacy and Protection Associations: Associations like the International Association of Privacy Professionals (IAPP) provide resources, data, and insights related to data protection and privacy practices.

Interpreting Benchmarking Data and Informing Strategic Decisions

Interpreting benchmarking data requires careful consideration of the context and limitations of the data. The board should work with security professionals to understand the nuances of the data and its implications for the organization.

- Identify Key Areas of Difference: Analyze the data to identify significant differences between the organization’s performance and that of its peers. Focus on areas where the organization is significantly above or below the industry average.

- Understand the Root Causes: Investigate the root causes of any significant differences. This may involve further analysis of internal data, interviews with security personnel, and discussions with industry experts.

- Prioritize Actionable Insights: Translate the benchmarking data into actionable insights. This may involve adjusting security controls, reallocating resources, or updating the security strategy.

For example, if benchmarking data reveals that the organization’s incident response time is significantly longer than the industry average, this could indicate a need to invest in improved incident response capabilities, such as training or automation tools.

- Develop a Strategic Roadmap: Use the benchmarking data to inform the development of a strategic roadmap for improving the organization’s security posture. This roadmap should Artikel specific goals, initiatives, and timelines.

- Communicate the Findings: Effectively communicate the benchmarking findings to the board. This should include a clear explanation of the data, the insights derived from the analysis, and the proposed actions.

Continuous Improvement and Feedback Loops

Implementing continuous improvement and feedback loops is critical for ensuring the ongoing relevance and effectiveness of security reporting to the board. This involves actively soliciting and incorporating feedback, adapting to the changing threat landscape, and continuously refining the reporting process to meet evolving business needs. This iterative approach ensures that the board receives the most pertinent and actionable information, enabling informed decision-making and effective oversight of the organization’s security posture.

Designing a Feedback Mechanism for Board Input

A structured feedback mechanism ensures that the board’s perspectives and concerns are consistently captured and addressed. This process should be easy to use, encourage honest feedback, and provide a clear path for incorporating suggestions into future reports.

- Post-Presentation Surveys: Distribute brief surveys immediately following each board presentation. These surveys should use a combination of multiple-choice questions and open-ended text boxes to gather both quantitative and qualitative feedback. For example, ask the board members to rate the clarity, relevance, and usefulness of the information presented on a scale (e.g., 1-5) and provide space for comments.

- Regular Feedback Sessions: Schedule dedicated feedback sessions, either quarterly or bi-annually, to discuss the reporting process in detail. These sessions can be held separately from the formal board meetings to allow for a more in-depth conversation. Invite the board members to discuss their specific needs, concerns, and any areas where they believe the reports could be improved.

- Anonymous Feedback Options: Provide an option for anonymous feedback to encourage more candid responses. This can be achieved through a secure online portal or a third-party survey tool. Assure board members that their anonymity will be protected to encourage open and honest feedback.

- Dedicated Feedback Point of Contact: Designate a specific individual or team responsible for collecting, analyzing, and responding to feedback. This ensures accountability and streamlines the feedback process. This point of contact should be able to explain the changes implemented based on the feedback received.

- Documentation and Tracking: Maintain a log of all feedback received, along with the actions taken to address it. This documentation should be readily available to the board to demonstrate that their input is being taken seriously and acted upon. This can be presented as part of the regular security reporting.

Strategies for Continuous Improvement

Continuously improving security reporting requires a proactive approach to incorporate feedback and adapt to the evolving needs of the business and the board.

- Regular Review of Feedback: Analyze the feedback received from the board on a regular basis (e.g., monthly or quarterly). Identify recurring themes, areas for improvement, and any specific concerns raised by board members. Use the feedback to prioritize changes to the reporting process.

- Iterative Report Design: Treat the security reports as living documents that can be updated and refined over time. Implement changes based on the feedback received and monitor the impact of these changes. This iterative approach allows for continuous improvement and ensures that the reports remain relevant and effective.

- Pilot Programs: Before making significant changes to the reports, consider conducting pilot programs with a small group of board members or stakeholders. This allows you to test the changes and gather feedback before implementing them across the entire board.

- Training and Education: Provide ongoing training and education to the security team on the importance of effective board reporting and the feedback process. This will help to ensure that the team is equipped to create reports that meet the needs of the board.

- Benchmarking Against Best Practices: Regularly benchmark the security reporting process against industry best practices and standards. This will help to identify areas for improvement and ensure that the organization is following the latest trends and techniques. Consider frameworks like the NIST Cybersecurity Framework or the ISO 27001 standard.

Incorporating Changes in the Threat Landscape and Emerging Risks

The threat landscape is constantly evolving, and security reporting must adapt to reflect these changes. This includes identifying emerging risks, assessing their potential impact, and incorporating relevant information into the reports.

- Threat Intelligence Integration: Integrate threat intelligence feeds and sources into the reporting process. This will provide the board with up-to-date information on the latest threats, vulnerabilities, and attack techniques. Subscribe to reputable threat intelligence providers, such as Mandiant Advantage or Recorded Future.

- Risk Assessment Updates: Regularly update the risk assessments to reflect changes in the threat landscape and the organization’s business environment. This includes identifying new threats, assessing their potential impact, and prioritizing risks based on their likelihood and severity. Consider using a risk matrix to visualize the risk assessments.

- Scenario Planning: Conduct scenario planning exercises to assess the potential impact of emerging threats on the organization. This involves developing different scenarios, such as a ransomware attack or a data breach, and analyzing their potential consequences. This will help the board understand the potential risks and make informed decisions about mitigation strategies.

- Proactive Monitoring: Implement proactive monitoring of the threat landscape, including social media, dark web forums, and security blogs. This will help to identify emerging threats and vulnerabilities before they can impact the organization. Use security information and event management (SIEM) systems, like Splunk or QRadar, to correlate threat intelligence with internal security data.

- Communication with External Experts: Engage with external security experts, such as consultants and researchers, to stay informed about the latest threats and trends. This can include attending industry conferences, participating in webinars, and subscribing to security publications. This provides an outside perspective on the evolving threat landscape.

Final Review

In conclusion, reporting security metrics to the board is not just about numbers; it’s about building trust, demonstrating value, and driving strategic alignment. By following the guidelines Artikeld in this comprehensive guide, security professionals can empower board members with the knowledge they need to make informed decisions, proactively manage risks, and ultimately contribute to the long-term success of the organization.

Continuous improvement, feedback, and adaptation to the ever-changing threat landscape are key to maintaining effective reporting and a strong cybersecurity posture.

Answers to Common Questions

What is the optimal frequency for reporting security metrics to the board?

The frequency should align with the board’s meeting schedule and the criticality of the information. Quarterly reporting is common, but more frequent updates may be necessary for significant incidents or emerging risks. Ensure that your reporting schedule is agreed upon by the board.

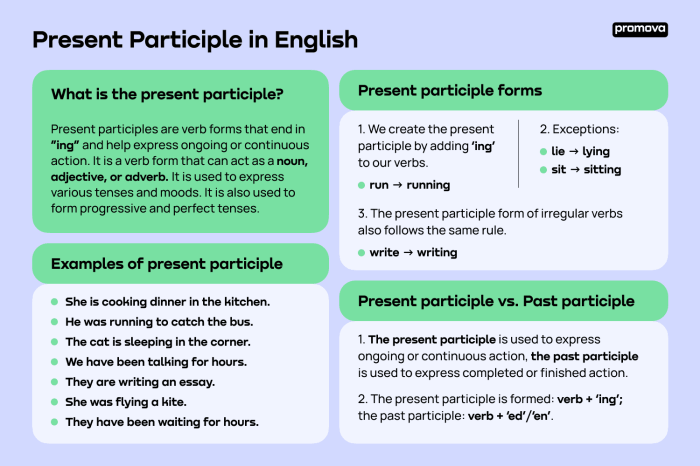

How can I ensure the board understands the technical jargon in my reports?

Use clear, non-technical language, avoid acronyms, and provide concise definitions for any necessary technical terms. Use visualizations and storytelling to translate complex data into actionable insights.

What should I do if the board has limited technical understanding?

Focus on business impact and risk exposure. Use analogies and real-world examples to illustrate security threats and their potential consequences. Tailor the report to their specific areas of interest and concerns, such as financial risk or reputational damage.

How do I handle questions from board members who challenge the data or findings?

Be prepared to answer questions with clear, concise, and data-backed responses. Have supporting documentation readily available. If you don’t know the answer, be honest and offer to find the information and follow up promptly.

How can I measure the effectiveness of my security reports?

Solicit feedback from the board on the clarity, relevance, and usefulness of the reports. Track changes in board members’ understanding of security risks and their level of engagement in cybersecurity discussions. Regularly review and update your reports based on feedback and evolving business needs.